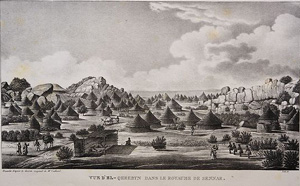

A village near Sennar in 1823

Big changes came to Sudan about 1500 AD. About 1490, the Shilluk people – who called themselves the Chollo and worshipped African gods – seem to have migrated north from around Lake Albert, in what is now Uganda, into South Sudan. The Shilluk formed a large kingdom along the Nile river in South Sudan, mostly herding cattle but also fishing and farming millet. The Shilluk pushed out the Funj, who moved north to invade and conquer the Nile Valley in North Sudan, and in 1504 established another big kingdom with its capital at Sennar.

By 1523, the Funj sultans converted from a mix of traditional belief and Christianity to Islam. Even though the Ottomans attacked them from Egypt, the Funj built a large and successful state, keeping written records in Arabic. The Funj traded with the Ottoman Empire to their north, with the Ottoman Red Sea port of Suakin to their east, and with Darfur to their west. But in the late 1500s, the Funj lost control of the important Nile region of Dongola to a revolt of the people they had conquered, who became known as the Abdallab.

Further west, the Dinka and the Nuer controlled South Sudan, and the Fur, who had ties to the Ouaddai further west in Chad, controlled North Sudan, known as Darfur. All of these people were nomadicor mostly nomadic cattle-herders. Dinka people lived mostly in and around an enormous wetland in western South Sudan.

In the 1600s, the Funj sultans became weaker as Funj traders became rich and demanded more power. The Shilluk king Odak Ochollo, in the early 1600s, thought that meant he could conquer more grazing land for his cattle further north. He made an alliance with the Sultanate of Darfur and with the Dinka against the Funj. But in 1630, the Dinka attacked Shilluk from the southwest. Instead of attacking the Funj, the Shilluk had to make an alliance with them against the Dinka.

Hanging with the Funj brought the Shilluk into closer contact with Indian, Ottoman, and European traders selling cotton cloth, pearls, and glass beads in exchange for cattle, honey, sesame seeds, ostrich feathers, and ivory. By 1650, the need for national defense against the Dinka was also making the Shilluk more of a unified country (perhaps under Funj control). The Shilluk king Dhokoth (Tokot), about 1680, controlled all trade through his country. Possibly he also controlled a blacksmithing industry making weapons and tools, trading ivory north to other Sudanese for iron ore. Dhokoth’s son Tugo, about 1700, built himself a small palace at Fashoda, with appropriate rituals. (This is just what Louis XIV was doing at the same time in France, though on a smaller scale.)

Darfur also grew stronger in the 1600s, influencing kingdoms in what is now Chad and Nigeria. But in the mid-1700s a civil war tore Darfur apart, and in addition Darfur lost battles with the Funj and with their eastern cousins, the Wadai of Chad.

By the late 1700s, the Funj were becoming subjects of the Ottoman Empire. The Shilluk, though, kept getting stronger. They established control of the places where traders crossed the Nile, and charged high tolls for shuttling traders across. (Compare the origins of Rome, or Paris, or London). The Shilluk captured many Dinka cattle, and took many Dinka women as slaves.

In 1820 the new ruler of Egypt after Napoleon, Muhammed Ali, entirely conquered the Funj kingdom along the Nile. About the same time, under the Shilluk king Nyokwejo (Tugo’s great-grandson?), an alliance of Dinka and Nuer people attacked the Shilluk from the west, and got control of part of the Nile River. Some Nuer settled west of the Nile, and even pushed into Ethiopia. The Ottoman troops stationed in Sudan began to raid and plunder the Shilluk kingdom, taking both cattle and people to sell as slaves. Pressed from both sides, the Shilluk became much weaker. Ismail Pasha, Muhammed Ali’s grandson, conquered nearly all of what is now Sudan in the late 1800s, and sucked wealth out of Sudan to make Egypt richer.

Muhammed ibn Abdalla

In order to get support from British troops against the Ottomans, the Dinka, and the Nuer, the Shilluk began to convert to Christianity in the 1800s. Some became Protestants, others became Catholics. The British also encouraged the Shilluk, instead of growing food, to grow a lot of cotton for British cotton mills. But mutations in the cholera virus brought terrible cholera epidemics to Sudan in the early 1800s.

Britain got a lot more interested in Sudan when they finished building the Suez Canal in Egypt in 1869, and a lot more British shipping went along the Red Sea. In 1879, the British took over Ismail Pasha’s empire, putting his son Tewfik Pasha in as their puppet, and in 1882 they forced all of Sudan into the British Empire. Sudan revolted under Muhammad ibn Abdalla. Abdalla and his successor Abdallahi won their battles, but they wrecked the country. Out of the eight million people living in Sudan, five million died from the war and the resulting famine and disease.

After the rebellion, the British still ruled Sudan. The British tried to control Sudan by encouraging ethnic and religious divisions: they encouraged Sudanese Muslims to hate the Christians, the Dinka to hate the Nuer and Shilluk, and so on. The British favored north-east Sudan over the rest of Sudan, building schools mostly there and drawing most government officials from there. These hatreds prevented the Sudanese from organizing successful rebellions.

With the end of World War II, Britain wasn’t strong enough to control its colonies anymore. The independence of Sudan was delayed because Britain refused to allow Egypt and Sudan to continue as a united empire. In 1956, Sudan ended up independent of both Britain and Egypt. But thanks to all the dividing, the people of Sudan all hated each other, and civil wars started almost immediately.

In 2011, South Sudan split off from Sudan into its own country, but the civil wars continue in both Sudan and South Sudan. The wars have made life very difficult there.