What is ivory? History of ivory: An elephant using her tusks

What is ivory?

Ivory is the same thing as elephant tusks (but see below). Elephants grow these long teeth to fight with, and to show how healthy and strong they are. Long ago, people just picked up the tusks from elephant skeletons, after the elephants had died. Later on, people wanted so much ivory that hunters started to kill elephants in India and Africa just to cut off their tusks.

To save the elephants, it is now illegal to kill them, or to sell ivory unless it is old ivory from a long time ago. Today it is illegal in all countries to kill elephants for ivory. People sometimes kill elephants for ivory anyway, but you can help stop them by not buying anything made of ivory.

History of hunting

African environment

Animals of India

More about teeth and bones

Selling the ivory

Sometimes traders sold the tusks to Egypt, Greece, Rome, or China for wine or silk or glass beads. Because ivory had to travel a long way to get to China or Europe, things made of ivory were very expensive. That made ivory a good thing to use for money: it was easy to tell if things were really ivory, and even small, light ivory things were expensive. Ivory workers often carved one elephant tusk into thousands of small beads. These beads were like the earlier beads made of rare seashells. But ivory was available to people who lived far from the ocean.

The invention of money

Art in ancient Egypt

Medieval art history

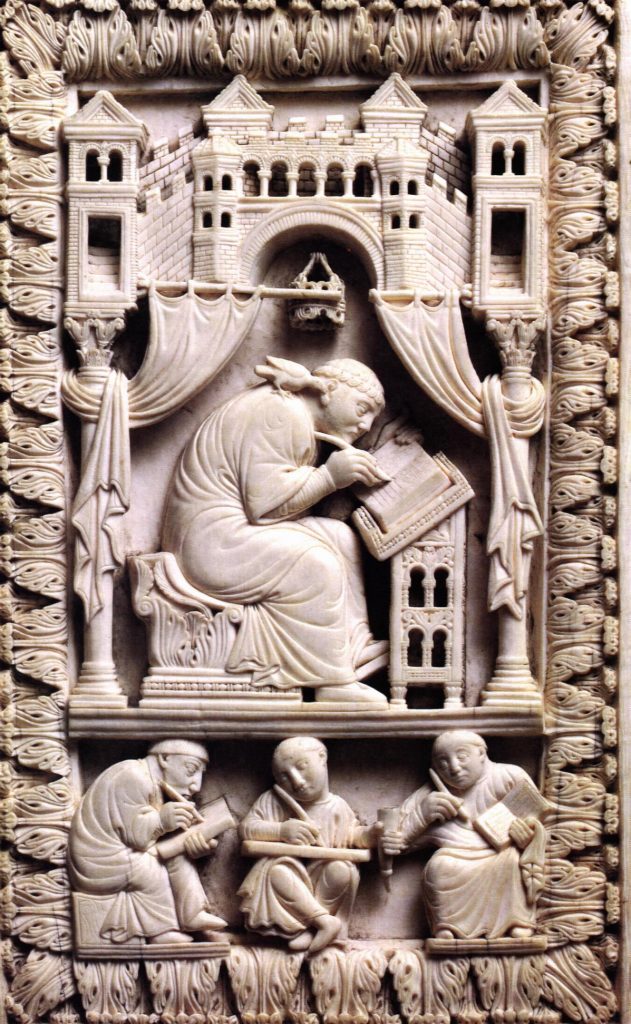

Ivory sculpture

A Roman doll with jointed arms and legs (this one is of bone, though, not ivory)

Artists also carved ivory into small sculptures. Most things made of ivory have to be pretty small, because elephant tusks are only so big. They’re about six inches across at the thickest part, and then they taper to a point. Often ivory statuettes are curved to fit the curve of the tusk.

Ancient Egyptian dice (Louvre Museum, Paris)

People also carved dolls out of ivory, using small pieces to make arms and legs and heads and fastening them to a wooden body with iron pins. They made dice and game pieces out of ivory, too.

Roman children’s toys

History of dice

History of ivory: Ivory statuette from Afghanistan, curved to fit the tusk

How to make big statues out of ivory

But when people wanted to make big statues out of ivory, they sliced the tusk into thin sheets, and then pinned the sheets of ivory to a wooden statue, to make an ivory statue. The statue of Athena in the Parthenon in Greece, for example, was covered with gold and ivory.

An Assyrian ivory from the 700s BC showing a Nubian man with an oryx, a monkey, and leopard skins, bringing them to the Assyrian king Assurnasirpal II

Artists also made boxes out of wood, and then covered them with very thin slices of ivory, so you would feel like you had a whole box made of ivory. This complicated picture was carved on to a very thin slice of ivory to be part of a box.

Pope Gregory the Great writing, from the 900s AD. Ivory, probably from Kenya.

(Now in Vienna Kunsthistorisches Museum)

Asian or African ivory?

At first most European and Asian artists used Asian ivory, from Indian elephants. But then they realized that African ivory, from African elephants, was easier to carve. Then traders started to buy African ivory, all along the East and West coasts of Africa.

Early Indian economy

East Africa

Medieval West Africa

Medieval African economy

Ivory was painted bright colors

A Late Antique ivory carving

Ancient and medieval ivories were usually painted in bright colors, to make them look more like real things. Today the paint has faded, so we see the ivories in their natural colors, but not the way the artists intended. Carved ivory statues and dolls were not white, but colored like Barbie dolls. Some of them would have been painted with dark skin, some as white people.

Ivory in the Middle Ages

Until 1300 AD, people in the Byzantine empire who wanted African ivory traded with the African kingdom of Aksum (modern Ethiopia and Eretreia). That’s why Aksum stayed a Christian kingdom until the 1300s AD. Aksum bought ivory from traders all over Africa to sell to the Romans.

The Byzantine Empire

More about Aksum

Walrus ivory in medieval Europe

Delilah treacherously cuts off Samson’s hair while he sleeps. Carved into a backgammon piece made of walrus ivory

But further north and west, people in the rest of Europe had a terrible time getting ivory in the later Middle Ages. People were getting richer. Everybody wanted to have something made of ivory. But there just wasn’t enough ivory coming from Africa for everyone who wanted it. Ivory became more and more expensive.

Lewis chessmen, carved of walrus ivory. They were probably carved in Norway, but were found in Scotland

So traders started to sell different kinds of ivory. They sold walrus ivory and whale ivory. It wasn’t as beautiful as elephant ivory, but it was easier to get. To get the walrus ivory and whale ivory, Viking traders bought the tusks from hunters in the north of Norway and Sweden.

Who were the Vikings?

Where did the Inuit live?

But by the 1200s AD, they needed even more walrus tusks than that. That may be one reason why they sailed to Iceland and Greenland. Possibly in Greenland, the Vikings sold steel knives to the Inuit in exchange for walrus ivory and whale ivory.

Ivory among the Inuit

The Inuit also carved ivory for themselves. Like people in Africa, Europe, and Asia, they made toys and small sculptures from walrus ivory and seal bones.

Inuit toys and games

Inuit walrus ivory carving (1800s AD)

Walrus ivory in East Asia

These Chinese Buddhist figures from the 11oos-1300s AD are made of mammoth ivory. Now in the Met (New York).

And at the other end of North America, Inuit people also sold ivory to East Asian traders. These traders sold walrus ivory in Korea, Japan, and China. Just like in Europe, these people also had trouble getting enough ivory to sell to all the people who wanted ivory beads and boxes. They used old mammoth ivory, from extinct mammoths, and they also used walrus ivory.

History of Korea

Medieval Japan

Song Dynasty China

More African ivory trade

But by the 1300s, African traders built new trade routes all through Africa, to get more elephant ivory. North African traders crossed the Sahara on camels to get the ivory. East Africans sold ivory to Iranian and Indian traders in ships on the Indian Ocean.

Medieval Islamic trade

Where do camels come from?

So there was not so much of a shortage of ivory anymore. By the end of the Middle Ages, Europeans and Asians went back to using mostly elephant ivory and not so much walrus ivory anymore. But then African hunters started to kill a lot of elephants to get enough ivory for everyone. Elephants started to be hunted to extinction. That’s why it’s illegal to buy or sell new ivory today.

More about medieval art

More about African trade

Bibliography and further reading about ivory:

Elephants, Ivory, And Hunters, by Tony Sanchez-Arino (2004).

Elephant: The Animal and Its Ivory in African Culture, by Doran Ross (1995).

Ivory in Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean from the Bronze Age to the Hellenistic Period, edited by J. Lesley Fitton (1993). Each chapter by a different specialist in ancient ivory.

Ancient Africa

Quatr.us home