Chinese numbers: number rods

Chinese numbers

People in China were using written numbers by about 1500 BC, in the Shang Dynasty. This is about two thousand years later than people began to write numbers in West Asia. It’s more than a thousand years later than people began to write numbers in India.

The Shang Dynasty

Writing in Early China

Early Indian mathematics

All our China articles

Nobody knows whether people in China thought of the idea to write numbers for themselves. Maybe they learned it from people in West Asia or India. Chinese people counted in base ten, like people in India. But the Chinese system was more efficient.

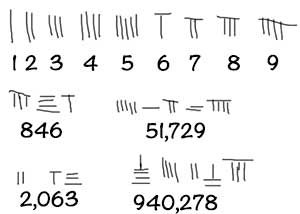

How to use Chinese number rods

In China, people wrote the number 465 like this: 4 times the symbol for hundreds plus 6 times the symbol for ten plus 5. This way of writing numbers made it easier to do addition and multiplication than the West Asian system, which used base 60.

West Asian numbers

For calculating, Chinese people used number rods: they arranged short bamboo rods in patterns, with the numbers from 1-10 represented by horizontal rods, while the tens place had vertical rods, and the hundreds were horizontal again (6-9 are upside-down versions rather than really horizontal). There was no mark for zero, but you left a space, and having two horizontal or two vertical places next to each other showed that there was a space left.

Number rods on the Silk Road

People in China were probably using this method of calculating with rods by about 500 BC, in the time of Lao Tzu. When traders started traveling on the Silk Road to Central Asia and India, about 200 BC, they brought this method of calculating with them to Samarkand and Varanasi.

Empires timeline 500 BC

What is the Silk Road?

Central Asian science

Chinese math textbooks

About this time, in the early Han Dynasty, Chinese scholars began to write math textbooks. Silk Road traders and Chinese government administrators used these math books – they needed to know how to keep accounts, survey land, and generally run the government. The earliest Chinese mathematical textbook is called the Nine Chapters; it includes a chapter on how to solve simultaneous equations (more than one algebraic equation at the same time).

The Nine Chapters

Volume of a cylinder

Volume of a sphere

Calculating pi

After the fall of the Han Dynasty in the 200s AD, the Chinese mathematician Liu Hui calculated the volume of a cylinder. By 450 AD, Zu Chongzhi built on Liu Hui’s work to figure out what pi was to seven decimal places, and to calculate the volume of a sphere (as Archimedes had done 700 years earlier).

Quadratic equations and zero

Under the Song Dynasty, there were many math colleges or institutes in China. In the 1200s, the mathematician Qin Jiushao worked on solving quadratic equations like x2 + 2xy + y2, cubic equations with x3 and on up to tenth order (x10) (which again had been done by Euclid in Africa about 1400 years earlier, or maybe even earlier by Pythagoras). Qin Jiushao also brought the use of zero from India to China, just about the same time that it first reached Europe.

What are quadratic equations?

Who was Euclid?

Invention of zero

The Chinese abacus

About this same time, people in China began to use the abacus. Nobody knows whether the abacus was invented in Iran or in China.

What is an abacus?

Medieval Islamic mathematics

If you knew how to use it, the abacus was very fast, almost like a modern calculator. Eventually most people in China stopped using the counting rods and started to use the abacus instead.

Craft project: make your own Chinese abacus

More about Indian math

More about Chinese science

Bibliography and further reading about Chinese mathematics:

Science in Ancient China, by George Beshore (1998). .

The Ambitious Horse: Ancient Chinese Mathematics Problems, by Lawrence Swienciki (2001).

Ancient China: 2,000 Years of Mystery and Adventure to Unlock and Discover (Treasure Chest), by Chao-Hui Jenny Liu (1996). Lots of activities , including a Chinese calligraphy set.

A History of Chinese Mathematics, by Jean-Claude Martzloff (1997). For adults. Explains the differences between Chinese and Euclidean (Greek) mathematics.

Zero: The Biography of a Dangerous Idea, by Charles Seife and Matt Zimet (2000).