I’ve had a week to think about the conference on ancient and American slavery that I went to at Yale last weekend, and I hope that has given me a chance to pull my thoughts together a bit. Still, these are impressions and ideas, not finished or polished. If you want an even less polished take on the conference, I live-tweeted it as it was going on; you can find the thread here. I am sure there are many other things I could say, and people whose work I should be singling out and appreciating, but maybe in a different post.

What I appreciated

There was some good work presented, for sure. Some people made a strong effort to present slavery from the point of view of the enslaved, to restore the voice of the silenced, or at least to consider things from that perspective.

Slavery as a form of work

Silver mining slaves at Laurion, near Athens

I was most struck by the way we discussed slavery for two solid days without once turning to the question of work. Someone listening in might never have realized that slavery is a way to control and compel labor. We talked about slavery in terms of identity and family relationships, in terms of sexual abuse, in terms of escape and value, of cultural loss and the loss of childhood, but there was very little about the work itself, or about why the Romans and the South chose that means of organizing work. (though David Lewis presented some ideas about why slavery and not hired labor)

Slavery in ancient Greece

And in ancient Rome

History of slavery

Slavery and reparations

A quilt made by enslaved African-Americans (1800s)

What I found most frustrating – and many black audience members found frustrating, though they were shushed and laughed at – was the unwillingness of the conference participants to look beyond the past and consider what our investigations of ancient and 19th century slavery had to tell us about the situation of African-Americans today, and how that situation might be remedied through reparations.

African-American slavery

African-Americans after slavery

Sojourner Truth

Slavery and wage labor

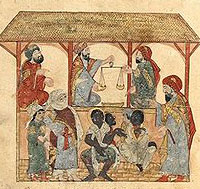

Slave market in Yemen (1300s AD)

I would also have loved to see some consideration of the many parallels between slavery and the modern system of wage labor, especially in the view that people today are not freely choosing to rent their bodies to corporations, but must work to live, to “make their living,” which is not a free choice at all. Employers have found increasingly effective measures to constrain this putative choice, from tying health care to your job, to paying such low salaries that it is impossible to save up for a move or even for a few weeks of unemployment, to irregular and unpredictable scheduling which prevents people from interviewing for other jobs.

Why people fall into debt

European economy in the 19th c.

But when I raised this issue in the discussion, the participants at the Yale conference, most of whom seemed to have little or no familiarity with the minimum-wage job market, reached back automatically to nineteenth-century abolitionist rejections of this parallel, as if those arguments were automatically right, or as if nothing had changed about the labor market since that time.

Enslaved African-Americans picking cotton. See the little girl?

Classics, white supremacy, and anti-racism

But my strongest feeling a week later is this: a new clarity that the most important and urgent anti-racist work classicists (and probably medievalists) can do right now is to actively work to dismantle the terrible wrongs our field has already perpetrated. For two or three centuries, classicists have been happy to use Romanization as an excuse to destroy the cultures of Africans, Native Americans, Indians, Australians, and Southeast Asians, and even to promote that destruction as a positive good.

The United States expands

The British in India

Brazil and colonization

History of Mozambique

For centuries, classicists have been teaching white children Latin from textbooks crammed full of propaganda about happy slaves and good masters, supporting the enslavement of African-Americans in the United States and similar situations in other countries.

Man beating a slave while another begs for mercy

For hundreds of years, classicists have encouraged the world to measure the Bhagavad Gita, the Enuma Elish, the Tao, the Shahnameh, and other classics only against the yardstick of Plato, Homer, and Virgil, and to dismiss them all as second-rate. In today’s United States, four and a half million people identity as Indian-American, while only a third as many identify as Greek-American, yet American high schools teach only Plato and Greek mythology and not the Bhagavad Gita or the Jataka tales, because that is “our culture.”

The Bhagavad Gita

Jataka Tales

Taoism in China

The Shahnameh

Whose culture? The culture of whiteness and empire, designed to exclude the colonized. Even the organization of the conference itself, implicitly connecting the Romans to the South, excluded other systems of enslavement in China and India and Africa, and reinforced our centering of Europe and European culture, though this went entirely unspoken and probably unnoticed.

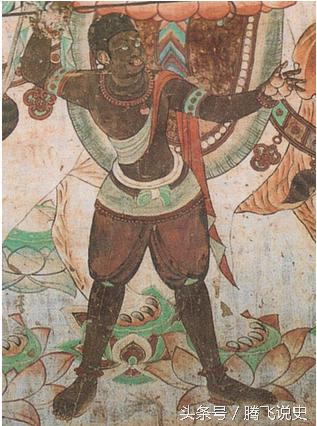

Slavery in ancient China

Slavery in medieval India

An enslaved African working in western China (T’ang Dynasty, Kunlun, ca. 700s AD)

So this is my commitment to work to change that: to work towards a world in which Americans can draw freely from the moral lessons of the many cultures of the world, in the same way that we already casually eat sushi, curry, tacos and souvlaki without worrying about foreign influences.

Want to see more of these posts? Follow us on Twitter @Quatr_us.

Support this blog by visiting our Patreon: your $5 monthly takes the ads off five pages on this site. When pledges reach $1000 ($900 to go!) I’ll take all the ads off the entire site, for all of our visitors.