A mutated snake with two heads

With all these new molecules like lipids, amino acids, RNA, and protein floating around in the oceans by around four billion years ago, there were a lot of new possibilities for what could bump into what. Sometimes a group of lipid molecules happened to stick together and make a lipid membrane, or even a lipid bubble.

Often RNA molecules bumped into lipids and broke apart into amino acids. Sometimes two RNA molecules got stuck to each other and made a new kind of molecule called DNA. Once in a while these RNA and DNA molecules happened to bump into a bubble of lipid molecules. Sometimes RNA and DNA even got stuck inside the bubble.

It turned out that DNA molecules were stronger than RNA molecules and didn’t break apart so much. So gradually there got to be more and more of these DNA molecules. And it turned out that the DNA and RNA that happened to get inside lipid bubbles were safer, and also didn’t break apart so much. Because more of the DNA and RNA inside bubbles survived, and more of the DNA and RNA outside bubbles broke apart, soon most of the DNA and RNA was inside bubbles – these were the first living cells.

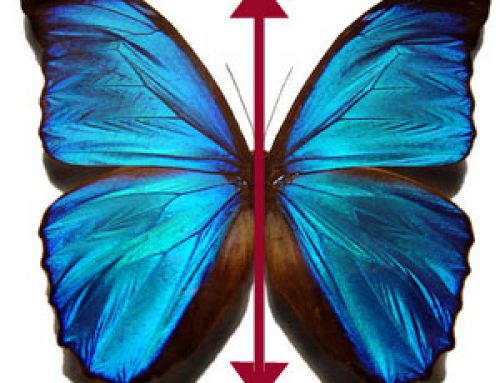

Now even inside the cells, the DNA and RNA still do often break apart, and then sometimes they stick together again in slightly different ways from before. Each time these breaks happen, that cell is a little bit different from the other cells around it. When that cell makes a copy of itself in order to reproduce, the new cells are like their mutated parent. Most of the mutations make the cell less likely to survive, and that cell soon dies off. Some mutations just don’t make much difference one way or the other. But once in a while a mutation turns out to be helpful to the cell. Cells with that mutation are more likely to survive. Then these new kinds of cells reproduce a lot of successful cells like them, while the older kind of cells just straggle along, and soon most cells are the new kind instead of the old kind.

One example of successful mutation is when, about 3 billion years ago, some cells developed the ability to photosynthesize. Photosynthesis is a complicated thing, and no one mutation could cause it to happen. But probably there were a lot of mutations that seemed not to make much difference, and then a few others that happened around the same time. The whole sequence of mutations may have happened more than once, in different cells, in different parts of the ocean. All together, these mutations let the cells make energy from sunlight. These solar-powered cells were so successful that there were soon a lot of them.

Other examples of successful mutations are when when cells began to use oxygen to make energy, and when some cells began to live inside other cells and cooperate with them to survive better, and when cells became able to stick together to make plants and animalsmade of more than one cell, and then when these animals began to cooperate with each other, like a school of fish or a herd of goats, so that more of them would survive. Many successful mutations have been ones that allowed creatures to cooperate better with each other, and people also have had mutations that favored cooperation, like the mutations that allow us to talk to each other.

Natural selection is when something changes by chance, and something new develops as a result. Usually the new thing doesn’t live long, but sometimes the change turns out to help the thing survive, and then there gradually get to be more and more of that thing, and fewer of the older kind that isn’t as strong or as cooperative.