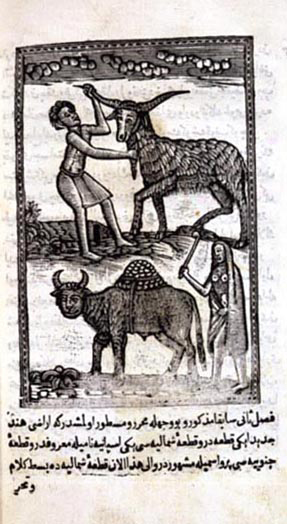

Ibrahim Mutafferika’s illustration of American bison (1728 AD)

One of the great new inventions of Renaissance Europe was the printing press with movable type. But one of the great disadvantages of the Ottoman Empire was that they didn’t start using printing presses. They didn’t publish books, pamphlets, or newspapers until much later – about 250 years later.

People were poorer in the Ottoman Empire than in Europe. There weren’t that many people who could read, or who could send their kids to school. Most people couldn’t afford to buy a book. So there was no market for the books a printing press could produce. Many smart people who might have become writers or scientists did not, because there wasn’t any way to support yourself as a writer or a scientist. (Isaac Newton‘s mother in England tried to take him out of school to be a farmer too. But he finished school and invented calculus instead.)

It wasn’t that they didn’t know about printing. Ottoman publishers knew about printing presses almost as soon as they were invented. Jewish people coming from Spain built a printing press in Constantinople in 1493, and another one in Thessaloniki in 1512. Christian traders had a printing press in Syria in the 1500s too. But only foreigners were rich enough to read and to buy books. So only foreigners used printing presses.

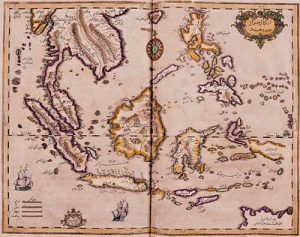

Ibrahim Mutafferika’s map of the Indian Ocean (1728 AD)

Another possible reason that Ottoman scholars didn’t use printing presses was that they thought most students shouldn’t learn from books. They thought students should learn directly from teachers. This was a better way of teaching and more scientific, with fewer errors. The way some teachers today don’t like online courses, some teachers in the Ottoman empire thought it was not a good idea to learn by reading books. There weren’t very many students in the Ottoman empire anyway, so the teachers could just teach them individually.

Some Ottoman publishers did try to start using printing presses, but they seem to have run into trouble. The one we know the most about was Ibrahim Mutafferika, originally from Hungary, who converted to Islam and began publishing in Istanbul in 1728. Ibrahim had to write an application letter to the Ottoman vizier Damat Ibrahim Pasha to get permission to use his press, and it seems likely that he was repeating arguments other printers had been making for years already. Ibrahim said that printing would help preserve books in case of disaster, and keep copyists from making mistakes in copying books. He also argued that printing would make books cheaper, and make the Ottomans the leaders of Islam.

The Vizier was interested in bringing Ottoman culture up to date, and Ibrahim got permission to print dictionaries and scientific books, but not religious books like the Quran. But when Ibrahim printed a controversial history of Egypt, the government shut down his press. Without a big market of people who wanted to buy his books, there was no political pressure to help Ibrahim publish his books, and he never did.