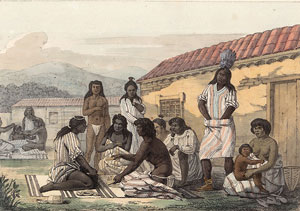

Mission Dolores, California – Native people playing the stick game (1816)

People always ask me, and you probably, and the world generally, whether this catastrophe or that one is like the fall of Rome. No, this isn’t the fall of Rome. Yet. But yes, we are following the path all empires follow, probably inescapably. First, a small group of leaders establish a new nation, and set about building their power by taking over their neighbors. You can do it by force alone, if you only want your empire to last a few years (think Alexander, Napoleon, the Athenians), but for a longer-lasting empire you have to get your neighbors on board with this (think Persians, Rome, Zhou Dynasty China). Rapid expansion provides a lot of opportunities to make fortunes, and fortunes are made. You can exploit newly conquered natural resources (the gold and silver of Spain, the tin mines of Britain, the enslaved populations of Gaul and Germany, the gold of Dacia). You can increase trade, both within your empire and with your new neighbors. The added wealth funds better schools, and better health, and you have a thriving middle class. More and more people get their freedom, and the vote. These healthy, educated men fight in your wars, and you win. You’re winners.

Chinese men working in the California gold fields in the 1800s

In Rome, that’s the last two centuries BC: the conquest of Greece, Gaul, Egypt. In the United States, that’s the 1800s, when we seized the gold of California and the Black Hills, the silver of Reno, and the seemingly unlimited oaks and walnuts and maples of the Northeast and the Northwest.

Strawberry Lake, in southern Oregon

But this doesn’t last forever. In a second phase, you have a long peace. You’ve reached some sort of natural limit to your power and size. Maybe the ocean or a desert or the Arctic (in Rome’s case, the Atlantic and the Sahara). Maybe land so far from home that communication is difficult (the Parthians). Maybe neighbors too strong to conquer (the Teutoberg Forest). You stop fighting wars and settle down. People like this peace, and things go along well. All the new people get integrated into the culture. They mind their own business, and lose interest in the government, and the government, now that it doesn’t need people to fight, loses interest in them. Slowly the rich get richer and the poor get poorer.

World War II Shipyard

Wars are far-off things, of little interest, fought by professional soldiers, often the sons and grandsons of soldiers; a separate class. Wars meet with increasing resistance from men who do not want to go fight, until the government abandons the effort to make them, and resorts to an all-volunteer (and increasingly inherited) armed force. There’s no longer any particular reason to win these wars; the men fighting them are more interested in their military promotions and in their own safety. So the wars end in stalemates, and seem to be more or less permanent backdrops for leaders to refer to in speeches. They’re expensive and pointless.

This Roman mosaic floor from Aldborough, in Britain, may be imitating Persian carpets.

In Rome, that’s the first century AD: the conquest of Britain, endless campaigns in Parthia and on the German frontier. In the United States, that’s the 1900s – the last of the fifty states join the Union, the draft becomes increasingly unpopular, and by 1975 it is abandoned in favor of a volunteer army. In Korea, in Iraq, in Afghanistan, we fight long, pointless wars which end in defeat or stalemate. We cut down the last of our old-growth forests, and run out of huge new natural resources to open up.

A third phase begins. The government, which is to say the rich, make up for the lack of new natural resources by extracting wealth from their subjects, and people gradually become poorer and weaker. The government resorts to authoritarianism, which is cheaper than representative government, and increasingly anything that isn’t forbidden becomes compulsory. Regionalism develops as people slow down their moving from one part of the empire to another. There are no more big initiatives, no efforts to inspire united action; the ship has become too big and heavy to turn. Soldiers, and anyone with ideas and energy, increasingly come from immigration from poorer neighbors.

Ostrogothic helmet imitating Roman helmets (ca. 400 AD)

In Rome, that’s the long second century: Trajan’s failed invasion of Mesopotamia and Hadrian’s retreat, and after that no more efforts. The army and the government rely increasingly on Goths and Africans, and on periodic distributions of money and food. In the United States, that’s where we are now. We, too, have declared victory in Mesopotamia and gone home. We, too, recruit our army increasingly among Mexicans and Central Americans, and our ideas – our doctors and inventors – from India and China and Africa. We, too, have lost interest in voting or running for office, which in any case makes less and less difference. We’ve become poorer and sicker, and we find it difficult to imagine large-scale responses to anything, other than distributions of food and cash. It seems possible this phase will last through the 2000s.

Crown of Recceswinth, a Visigothic king

What comes next? Big threats emerge, and the government proves incapable of organizing a response. There are climate changes, plagues, invasions by neighbors who have noticed your weakness. The government tries to rally the people, but they are poor and sick and used to obedience and passivity, and they do not respond. Regionalism continues to build, and people increasingly turn to a local government they can still influence, and look to them for solutions instead of the far-off imperial power. The government becomes too poor to pay the army adequately, and soon the army exists more on paper than in reality.

In Ostia, after the aqueducts broke down, people dug wells for water right in the middle of the street.

In Rome, that’s the crisis of the third century – the 200s and 300s AD. It brings renewed German and Parthian invasions, the first big smallpox epidemic, and possibly climate change as well. Here, too, we can expect the 2100s and 2200s to bring serious climate change, and increased military and trade challenges from Central America and China, if not other places as well. Probably we’ll see mass immigration from Central America, partly by force, which will provide a new generation of leaders who work to resist China (which will have its own problems with climate change as well.) We’ll see regional civil wars within the United States, probably starting with fights over the dwindling supply of fresh water. The form of the federal government will technically continue, while all real power lies with arch-governors who control shifting groups of states. The decline of the interstate highways and trains, which the federal government can’t afford to maintain, will increase regionalism. Instead of joining the moribund federal armed forces, people sign up with their local Guard, which fights for real things they care about: water rights, and the defense of their own families. Without an empire, everyone will be poorer, and more at risk of being captured and enslaved.

Probably, therefore, by 2200 we can expect the United States to be functionally collapsed. The good news is, this probably won’t happen in your lifetime, or your children’s lifetime.

While I do agree that we could become a failed state, the 2018 elections indicates another possibility. The increased participation in the 2018 midterm elections may continue this year. Trump I believe is a wake up call. My hope is that our electorate takes advantage of this upheaval to push The pendulum toward increasing equality, rather than decreasing equality.

I really enjoy your site. FYI I was unable to use the monthly subscription button.

Sorry, I’ll try to fix it! Thank you for your interest!